A scenario technique approach to the use of wearable devices by tourists at the destination

by Diana Fernanda Ortiz Rincon, Ashan Sasitha Abeyra and Eleonora Tommasini

Introduction

In the last few years mobile devices such smartphones and tablets have played a central role in our everyday life. Regarding the tourism industry they also contribute noticeably to the tourist’s experience, addressing not only the inspiration and planning stage, but also the experience on-site (Benckendorf et al., 2014). However, wearable devices are considered to be the technology of the future, which will definitely change the way people experience their surroundings.

Wearables are described by Jhajharia et al. (2014) as a device that becomes one with accessories and clothes and therefore can be easily worn by people. It can take various shapes that range from a wristband, a watch, to a pair of glasses that engage with the surroundings.

Today personal technologies are becoming more wearable, implying potential changes in the way users interact with technology and with each other (Tussyadiah, 2013). Relevant for the field is the research of Ihde (1990) about “non‐neutrality of technology-mediated experiences”, which states that technologies are set between humans and the world and therefore they can change human experiences, enhancing some aspects or reducing others. According to Ihde (1990), through embodiment, technologies will be to extend the sense perception of the users, giving the opportunity to conduct many activities at the same time, such as watching an attraction while accessing to different information (Tussyadiah, 2013). An important research in the field of wearable devices and tourism experience has been conducted by Tussyadiah (2013), who identified through a content analysis five categories representing patterns of motivation to use Google Glass as wearable devices for travel- related experiences.

Choudhary, Bhag & Walia (2014) argue that while wearable technology will not be replacing smartphones any time soon, and likely will not be widely used for years to come, the future is bright for this industry. Therefore, understanding the future implications of wearable devices and their impact on the tourism industry and consequently on the tourist behavior is a necessity.

The goal of this study is to determine the possible future scenarios of the use of wearable devices by tourists on site, by focusing on two types of wearable technology: smart glasses and smart watches, devices that facilitate practical functions including communication, navigation, health monitoring, fitness tracking and augmented reality. In addition, this research also aims to bring a meaningful contribution to the existing literature regarding the future of the wearable devices used by tourists on site and its effects on tourist behaviour.

Methodology

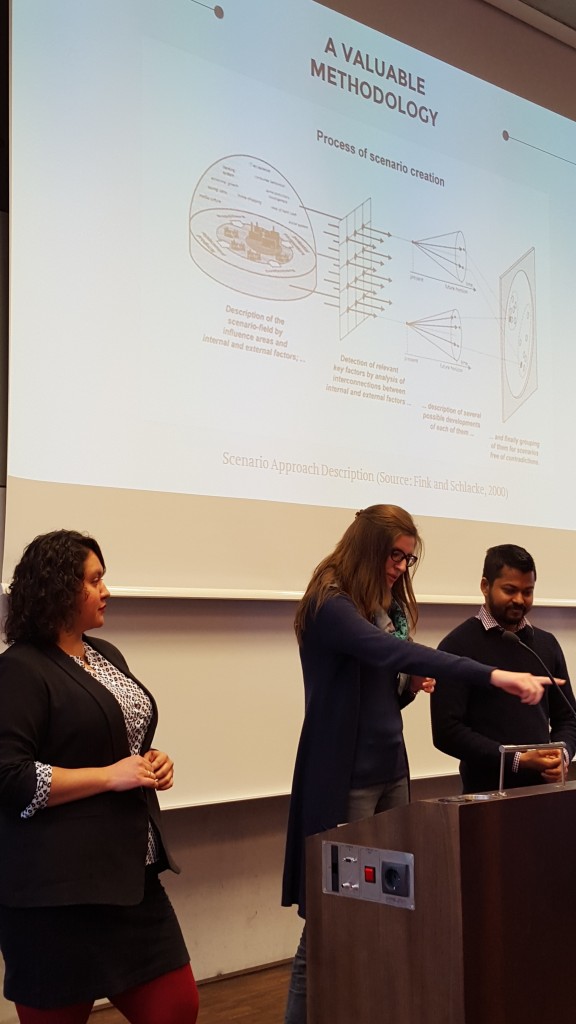

When it comes to determine future development of a particular issue, the scenario approach is described as one of the most useful tools among the future research methodologies, because of its ability to consider a wider range of possibilities and possible future directions otherwise ignored (Shoemaker, 1995). This methodology is a scientific but at the same time creative process that aims at generating an array of scenarios based on possible future developments of the variables that build the system (Fink & Schlake, 2000).

Starting point of the scenario approach is the assessment of the most influential and critical factors through a structural analysis, in order to be able to identify factors part of the base scenario (Godet & Meunier, 1999). As the literature suggests, these variables can be identified through a team process that stimulates creativity thinking, an open exchange of ideas (Fink & Schlake, 2000; Godet & Meunier, 1999) and contribute in reducing the degree of subjectivity (De Jouvenel, 2000). For this reason, one of the most suitable method for the data collection was identified in the focus group practice, due to its ability to raise different opinions from the presence of members with diverse values and believes (Van der Heijden et al., 2002). The organized focus group saw the participation of 10 master students of the Salzburg University Of Applied Sciences, with good understanding of technology in tourism, since it is highly advisable to address somebody that possess adequate knowledge of the issue and might also be involved in the system (Godet & Meunier, 1999). Within this context, the PESTEL analysis provided a good framework to support the formulation of questions that covered different sphere of impact of wearable devices, in order to generate a more comprehensive array of factors that form the base scenario (Van der Heijden, 2002). Finally, 21 different factors were identified and rated pairwise following the order from the y-axis to the x-axis, according to a scale from 0, absence to 3, strong influence (Schüll & Schröter, 2013).

From these 21 factors the research team conducted the following observations:

- Software (2) and Hardware (9), Network and Infrastructure (10), Comfort and Embodiment (8) are active or also named influential factors (1st quarter). These factors, especially the first three, influence the system much more strongly than they are influenced.

- Functions and Usages (5), Dependency (6) and partially 3rd Party Information (14) are critical, dynamic or relay factors (2nd quarter). These variables are very influential and at the same time very dependent on the others.

- Experience Enhancement (4) and Crisis Management (16) are reactive but passive factors (4th quarter): they are influenced more strongly than they act on the others.

- All the remaining factors are falling in the 3rd quarter of the map and are the so called buffering, excluded or lazy factors. They have a low influence and low dependency, with major concern to the ones falling in the lower side. Among the excluded factors for their quite passive tendency we find Terrorism and Criminality, Use permit, Legality of Use, Dependence on Smartphone and to some extent Market, which has been employed in the scenario description to address the level of competition, in connection with the price variable.

The following step saw the conduction of a morphological analysis which saw the listing of two or more future alternatives for each factor and a consecutive consistency analysis. For many factors the researchers provided two manifestations according to a future situation that is rather stable and unchanged and its possible further development, e.g. referring to the hardware, it was assumed to either face an increase in capabilities or to maintain the same ones as current. In order to identify how well two different developments could suit together in the future, the research team proceeded with the attribution of a contingency rate. The ratings were attributed considering the likelihood of a pair manifestation in a time lapse of 5 years, based also on the opinions and the issues raised by the focus group participants. With the fulfilment of the consistency matrix, the software calculated all the possible combination that could be generated by combining all the different manifestations.

Fundamental for the scenario selection is its degree of plausibility and consistency (Van der Heijden et al., 2002). Generally the uncertainty of a future development depends on the number of possibilities that are generated: the more outcomes, the greater the uncertainty. Within this case it was therefore advisable to apply a more flexible strategy for the scenario selection, in order to assess a major number of choices (Godet, 2000). Therefore, the adopted strategy took into consideration four different scenarios according to a best, a worst and a surprise-free case (Schüll & Schröter, 2013), based on the driving forces previously identified in the structural analysis as most active and independent factors on the first quarter of the matrix (Van der Heijden et al., 2002).

Findings

Within the frame of the use of wearable devices by tourists on site the research shows that software, hardware, network & infrastructure and comfort & embodiment are the most influential and independent factors. In addition, variables such as functions & usages, dependency and access to information by third parties, were identified as critical, very influential but also highly dependent on other factors.

The four scenarios presented aim at providing an overview of possible future situations concerning the use of wearable devices by tourists on a destination. The first and the last scenarios have the highest consistency rate and are therefore the most plausible, based on the ratings assigned in the structural and morphological analysis. Both scenarios are actually based on the assumption that software and hardware of wearables will undergo further development, becoming more functional, sophisticated with a higher degree of comfortability, together with the improvement of network and infrastructure that provide internet access to those devices. For instance, the European Union claimed the abolishment of extra roaming fees by 2017 for all its countries, enabling its citizens to call, send messages and surf benefitting from the same tariffs also when abroad (European Commission, 2016). Based on this statement and the currently development of these technologies, there is a higher probability that the future use of wearable devices on site might reflect part of these aspects. The two scenarios are shaped starting from quite similar influential future developments. However, the third party access to private information plays a big role in their differentiation: while in the Awesome Scenario wearables pose no major threat to privacy and protection of private information, the Evil Scenario presents a possible future where the use of wearables facilitates a permanent intrusive access and acquisition of personal private information by third parties through software and social networks.

The scenarios Meh and Grumpy on the other side, present lower consistency rates. This indicates a reduced degree of credibility and are developed on the assumption that software and hardware of wearables will not undergo major further developments, but rather maintain their current features. Also the future projection addressing network and infrastructures indicates an unchanged situation, without any further improvements regarding Wi-Fi coverage or the availability of more convenient roaming possibilities. On one side, we find the Meh Scenario picturing a rather unchanged situation where the majority of the tourists are still using their smartphones while on site: even though being comfortable to use, the limited possibilities offered by wearables contributes to a limited adoption only by an elite of tourists, who are either more technology oriented, or take advantage of the possibility to keep track of their health conditions. On the other side, the Grumpy Scenario portrays a situation, where wearable devices fail to provide tourists an overall experience enhancement, due to its reduced functionality and a high degree of discomfort while wearing them. Moreover, it will result on tourists’ dissatisfaction when using wearables as they will be paying a premium price for functions that are already available in other devices.

Conclusion

Wearable devices are gaining popularity around the world in both personal and business usage across many fields. In tourism sector, these devices are expected to have an effect on how a tourist would look, communicate and interact with their environment in the future. This study was conducted using the scenario technique in order to identify future possibilities of the use of wearable devices by tourists on site. Out of a vast number of possible scenarios generated, the four scenarios chosen and described: Awesome, Meh, Grumpy and Evil depict future instances within highest and lowest consistency rates, offering the reader an overview on four extreme possible scenarios at different degrees of plausibility.

As noted earlier, wearable devices are still at an early adopter stage in terms of public and commercial use. However, as the famous Greek philosopher Seneca claimed: “if one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favourable”, the researchers aimed at assessing a wider range of possible directions that the development of wearable devices might follow in the near future.

References

Benckendorf, P. J., et. al (2014). Tourism Information Technology, Cabi Tourism Texts, Wallingford, UK.

De Jouvenel, H. (2000). A Brief Methodological Guide to Scenario Building. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 65, 37–48.

European Commission (2016). Roaming Tariffs. Retrieved January 2016 from https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/roaming-tariffs

Fink, A., & Schlake, O. (2000). Scenario management—An approach for strategic foresight. Competitive Intelligence Review, 11, 37–45.

Godet, M. (2000). The Art of Scenarios and Strategic Planning. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 65(1), 3–22.

Godet, M., & Meunier, F. (1999). Structural Analysis. Futures Research Methodology—V3.0, 0–48.

Ihde, D. (1990). Technology and the Lifeworld: From Garden to Earth. Bloomington, University Press, Indiana, USA.

Jhajharia S., Pal S.K. and Verma S. (2014) Wearable Computing and its Application. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technologies, 5 (4), 5700-5704.

Schüll, A. E., & Schröter, W. (2013). Guideline for the performance of participatory scenario processes in INTEGRAL.

Shoemaker, P. J. H. (1995). Scenario Planning : A Tool for Strategic Thinking. Sloan Management Review, 36, 25–40.

Tussyadiah, I., (2013). Expectation of Travel Experiences with Wearable Computing Devices. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014: Proceedings of the International Conference in Dublin, 539-552.

Van der Heijden, K. (2002). The Sixth sense: accelerating organizational learning with scenarios.